Bush Food may hold key to Climate Change Adaptation

Aussie native foods present a necessary path for the future

Our dietary choices are a major contributor to climate change. New research has found that Australia is one of the countries with the greatest potential to reduce diet-related greenhouse gas emissions.

Aussies love to incorporate a variety of international flavours and cuisines into our diets. But what about our own native Bush Foods?

“Bush Food”, or “Bush Tucker”, is the name given to the edible plants and animals native to the Australian continent, the vast majority of which are hard to come by. Many are held in private knowledge by Traditional Custodians, and not available on the supermarket shelves.

Foods like bush tomatoes, finger limes, quandong and old man saltbush have been harvested by Traditional Custodians for tens of thousands of years - and are now becoming more popular in the Australian culinary scene as a more environmentally friendly alternative than those we eat every day.

Many of these foods hold important cultural significance to Aboriginal communities. The Bush Food industry offers an important source of employment for Aboriginal people, and sustains traditional cultural knowledge and practice within these communities.

Bush Foods put climate sustainable ecological farming back into the hands of Indigenous Peoples - who are among the first to face the consequences of climate change.

In recent decades, Australia has seen a shift towards higher temperatures and lower winter rainfall, which has already started to affect the price and availability of what’s on our plate.

According to a recent report from the Australian Government Department of Agriculture, over the past decade there has been a 23% annual loss in the agricultural industry, directly caused by changes in seasonal conditions.

Depending on how much the world adapts to climate mitigation strategies, there are different possible future outcomes. But for each emissions scenario, there is a prediction for a loss of seasonal rainfall for Australian farmers.

The Australian Government says the threat of climate change is leading a “transformational change” in the agricultural sector - and Aussie farmers are already starting to adapt to tougher conditions, and a highly uncertain future.

Consumer power is a major driving force behind the shift towards more environmentally conscious agricultural practices.

- According to the United Nations, Indigenous people are among the first to face the consequences of climate change. Due to their close relationship with the environment and its resources, climate change exacerbates the marginalisation, discrimination, unemployment, and loss of land and resources.

- A 2021 report from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) found that climate change is already affecting food security, through changes in temperature and rainfall.

- 84% of Aussies are in favour of taking action against climate change.

- The global population is estimated to reach almost 10 billion by 2050 - that is 3 billion more mouths to feed. It is estimated that global food production may need to double to meet this demand.

- Increased temperatures can lead to significant loss of nutritional and calorie content in food - especially in iron, protein, zinc, and calcium.

- Australia produces around 93% of its own food. Through these impacts on food production, the agricultural sector bears a greater economic loss from climate changes than any other sector.

- Australia is part of the International Food and Land Use Coalition, a global collaboration to work towards sustainable food and land use systems by 2050.

- Ninety per cent of Australian consumers want sustainable products.

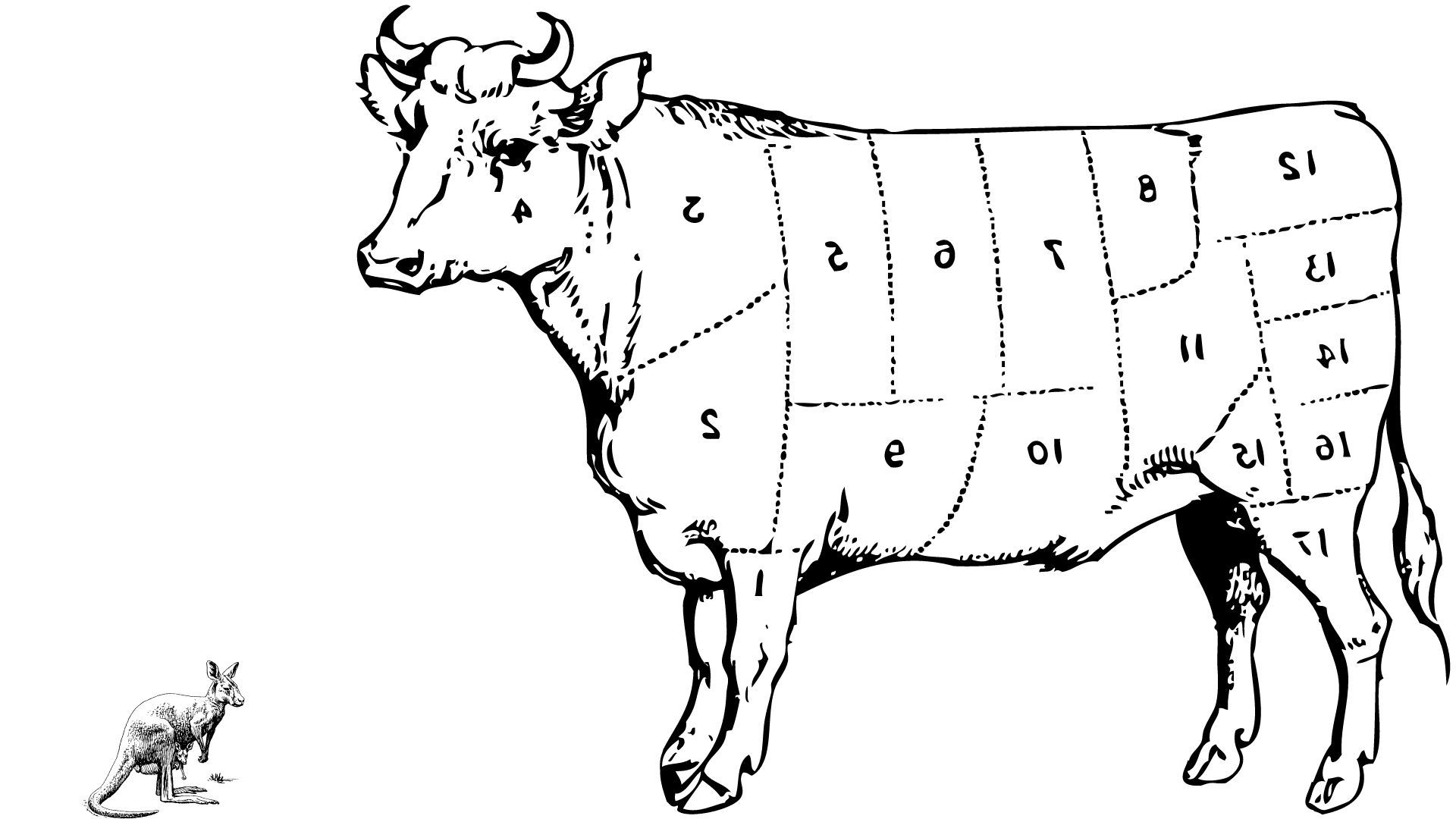

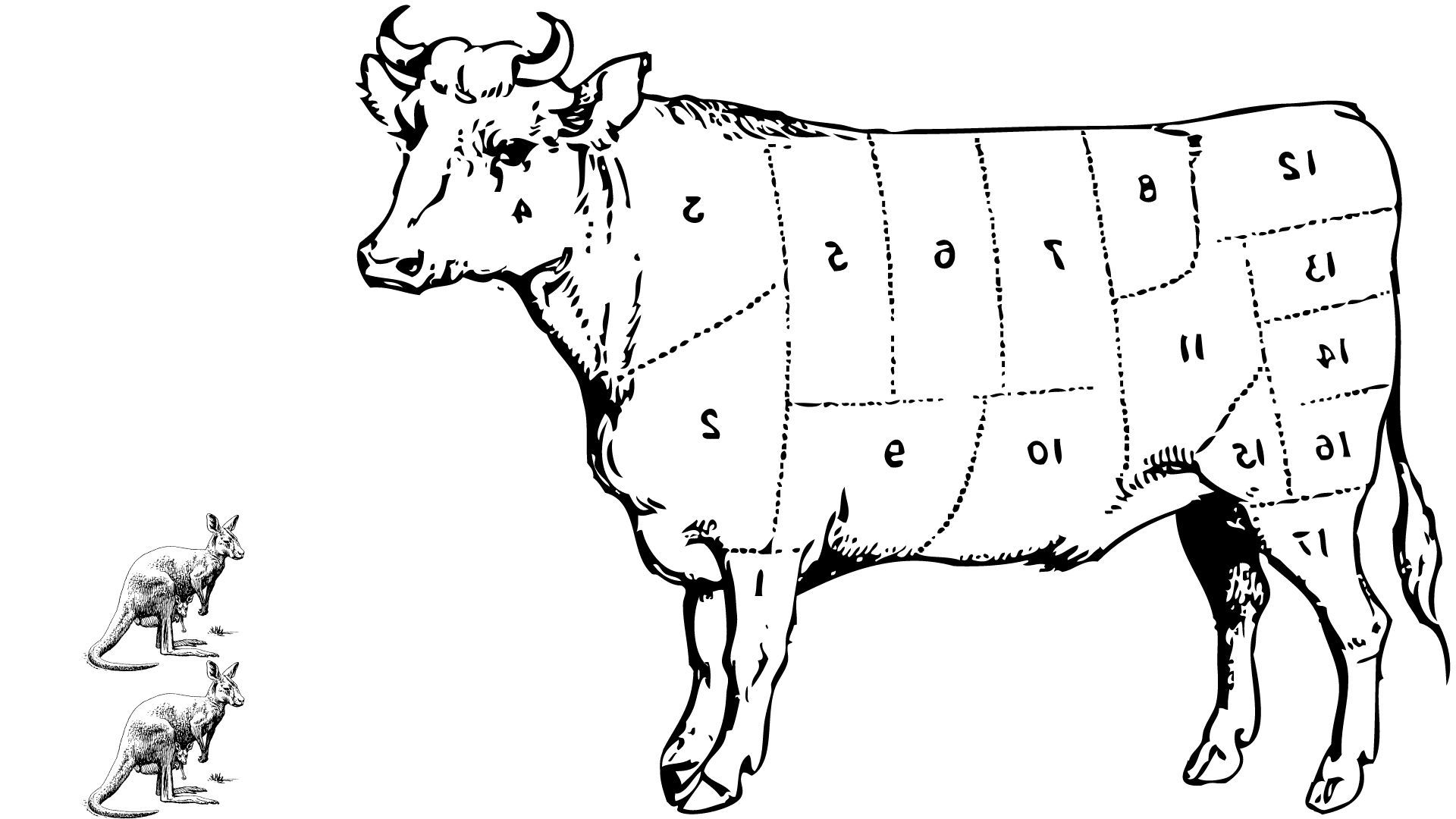

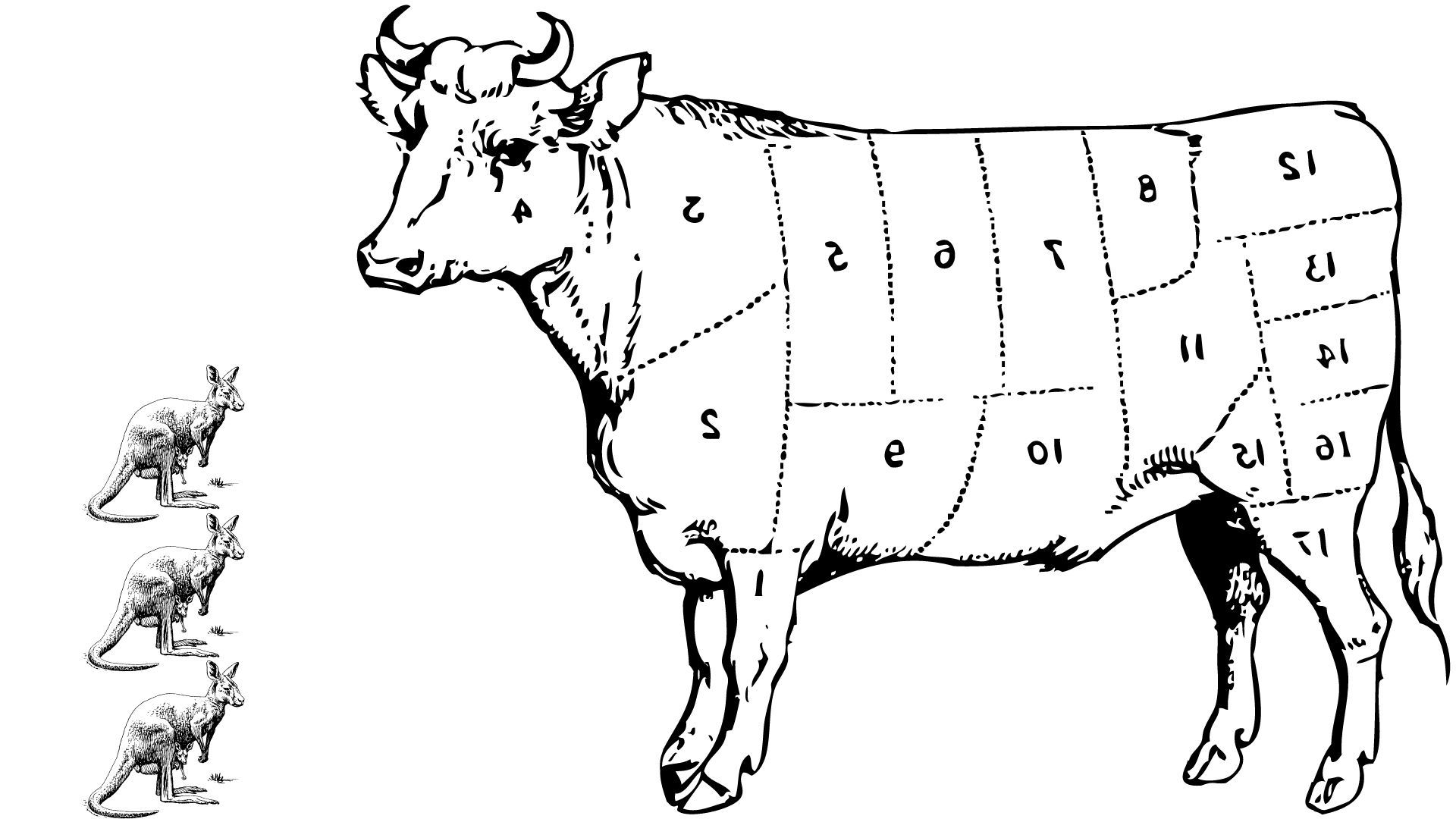

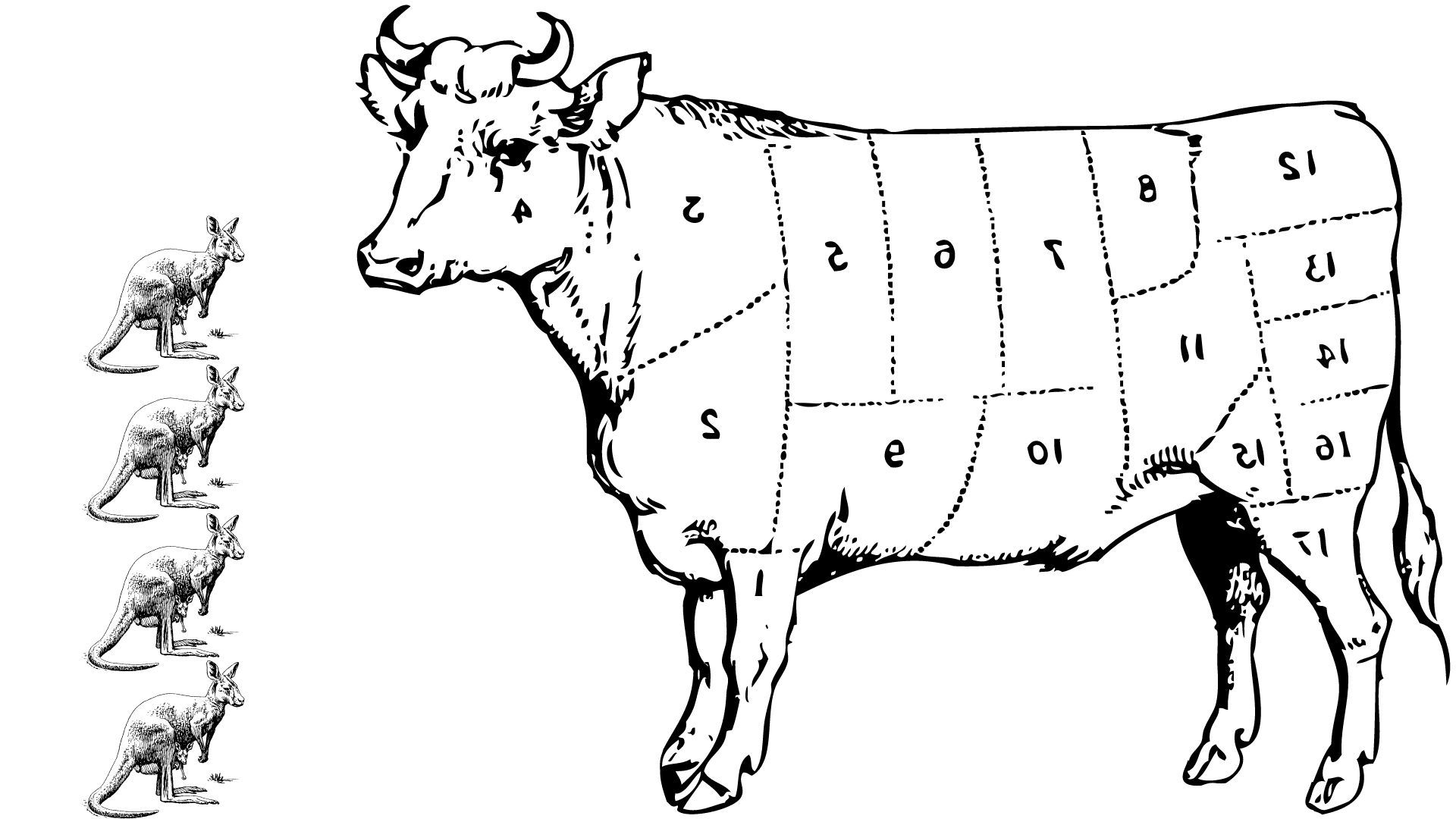

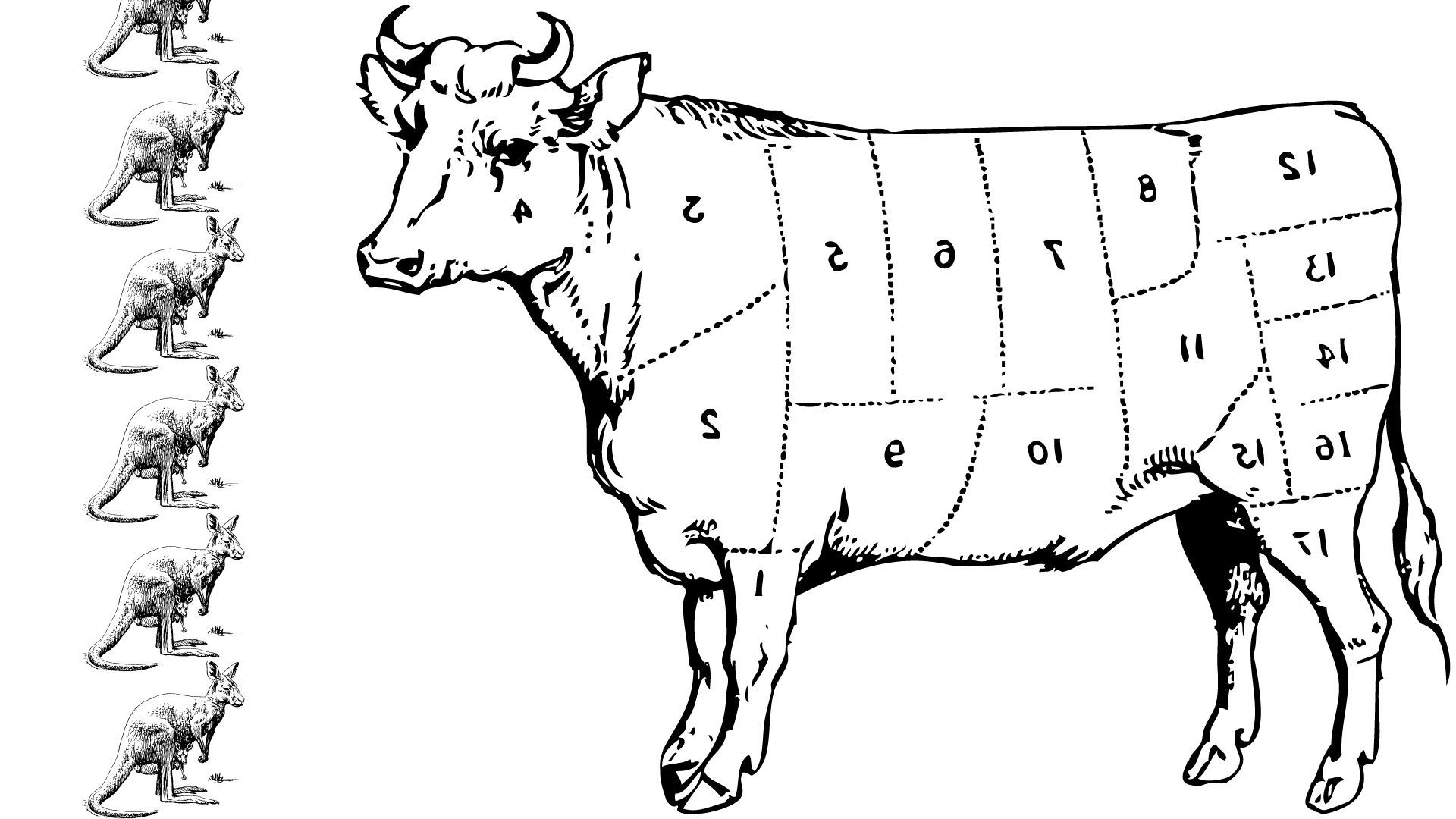

The first comprehensive carbon footprint league table for food shows the difference in CO2 emissions between different crops.

Researchers at RMIT University and Lancaster University found that beef production has approximately five and a half times larger carbon footprint than kangaroo meat. 4.1kg of CO2 is produced for every kilogram of kangaroo meat - compared to 22.7kg of CO2 produced per kilo of beef.

This is partly because the supply chain - from the farm to your table - requires less transportation for local produce, and because cows are methane producing animals (which is a greenhouse gas). But it is mostly due to the fact that native species are more adapted to the harsh Australian landscape - an environment of long periods of dry weather and varying levels of rainfall. Many native species are more naturally adapted to be hardy to changes in temperature and rainfall, and have a wider distribution over a range of climate conditions.

Professor Melissa Fitzgerald talks about the environmental sustainability of native foods

Melissa Fitzgerald, Professor of Food Sciences at the University of Queensland is working with Indigenous chef Dale Chapman on a project studying Bush Foods. She says that native species have evolved for millions of years to suit this environment.

“Because we’re using plants that are endemic to each area, we’re using plants that are very well adapted to those environments... This makes it so much easier to grow... Their water requirements are adapted to the climate, and their nutrition requirements are also adapted to what they can get from the soil. It is much more environmentally sustainable than growing an introduced crop.”

This means that many species, as a food choice for consumers, are far more in balance with the natural ecosystem and less harmful to the environment.

Dr Sean Bellairs talks about Australian wild rice and climate change.

Dr Sean Bellairs is a Senior Lecturer at Charles Darwin University, doing research into restoration ecology, ecosystems, and commercialisation of native plants. He is studying how native edible species like wild rice might hold the key to genetically adapting commercial rice varieties to changing climate conditions, because these wild rices grow over a range of climates.

“In terms of climate change impacts on these species of rice… They could be quite important for adapting commercial rice and making it more tolerant to high temperatures or to diseases as a result of climate change… and really valuable to making it more resistant to future environmental changes”.

According to a new report from the Australian Climate Council, the yield of commercial crop species like rice and wheat are significantly reduced at temperatures of more than 30°C.

Use the interactive map below to see where you can find these native species growing in the wild. The colour of the image corresponds to the distribution of the plant. Click on the image to read the description and find out more.

Daniel Newchurch talks about growing native food in harmony with nature

Traditional Indigenous techniques are being explored by farmers working towards habitat restoration and a more balanced ecosystem.

Narungga farmer Daniel Newchurch is using ancestral knowledge of native plants in running his family-owned farm, Newchurch Horticulture, which specialises in edible natives. He grew up on an Aboriginal Mission on the York Peninsula, and is now applying traditional harvesting practices towards a new system of growing in his enterprise today. For Daniel, the emphasis is that his farming techniques must be “hand in hand with nature”.

“If we look after [the environment], it looks after us. That’s basically the motto that we go by. You look after it, take what you need - and don’t rid the land of everything that it’s got.”

Newchurch Horticulture uses an ecological farming system that allows for a restoration of the natural ecosystem. On the 60 acre farm they cultivate edible bush plants using conventional farming techniques, alongside bush foods that are growing wild.

“We don’t need a large watering system like conventional farms do, because they’re native. We grow what is local to our local area… The soil is getting richer, and we’re seeing wildlife come back.”

“We grow them wildly, and we do harvest them - but the reason that we’ve done that is for the wildlife to return. So, [it’s] a bit of a harborage for them.”

Professor Melissa Fitzgerald talks about the importance of keeping Indigenous knowledge and ownership of native plants within Indigenous communities.

It might be surprising to learn that at present, only 1% of the Aussie Bush Food industry is Indigenous owned.

According to the United Nations, Indigenous people are the first to face the consequences of climate change due to their close relationship with the environment and its resources.

Ensuring that the ownership of native products remains in the hands of Traditional Custodians could counteract the risks that climate change poses to Indigenous Australians - including unemployment, economic marginalisation, and loss of land, livelihoods and resources.

Professor Melissa Fitzgerald is working with Indigenous chef Dale Chapman to ensure that new Bush Food products are brought to market to bring the economic benefits back to Traditional Owners.

The five-year project is thanks to a $1.5 million grant from the Australian Research Council, funding research and infrastructure necessary to bring native edible plants to the public. Professor Melissa Fitzgerald says that the majority of products that they are researching are held in private knowledge by Traditional Custodians, and are not on the supermarket shelves.

"At the moment, the Bush Food Industry is worth millions and millions of dollars, and only one percent of that goes to Indigenous People. If you're trying to buy something from an Indigenous business, you have no way of knowing whether that business is Indigenous owned or not".

"The University of Queensland has decided to hand all of the intellectual property to the indigenous community."

Dominic Smith of Pundi Produce talks about farming ecosystems, culture, and food as medicine.

Indigenous farmer Dominic Smith is passionate about the sustainability of the native food industry, conservation and land management.

From the Yuin nation of the Black Duck People in NSW, Dominic runs Pundi Produce, in the woodlands of South Australia. He is passionate about using plants as medicine, and restoring the connection between Indigenous people and the land. He is aiming to “get people back on Land and learning about Culture, medicines and ecosystems.”

“If we can look after the land and get what we need, [and] also the animals as well, it makes a little haven for them, an oasis. So I get wildlife coming in now - lizards, birds, even ladybugs come in for the Rivermint to try and eat [the bugs] there… it’s all about using what’s around.”

“I just think we are part of nature and we should learn about nature. By looking after nature we are looking after bugs, birds, and the people at the same time”.

Award-winning Chef Andrew Fielke talks about the environmental impacts of kangaroo meat.

Award-winning chef Andrew Feilke is working with Dominic Smith to run distribution company Edible Reconciliation. Andrew has been in the industry for the past 35 years, and says that he has seen a big shift.

“In the 90s it was all about awareness from a restaurant perspective… it has come back really strongly in the last 5 or 6 years, and this time it’s really changed for the better in terms of becoming a really entrenched and important part of a truly unique Australian cuisine”.

He says that both Aussie and international foodies are becoming more interested in food choices that have less impact on the environment, particularly kangaroo meat.

“More people are understanding that it is such an important way to go for the future of our country… To produce and farm meat that doesn’t have such an impact on the earth as, say, cows and sheep do.”

Daniel Newchurch talks about the future of farming in Australia

Indigenous farmer Daniel Newchurch looks forward to a more sustainable future of farming.

“Our big goal is to really be a model for future farmers… For us, it’s a fifty - fifty between having a business where we sell the product, but also having a business where we educate people about the product. It’s a new model of where future farming needs to be... By growing native, we are successfully returning the earth back to where it needs to be.”