Refuge

The Untold Story

Born as an Afghan refugee in Pakistan, Zakiria Tahirian has never set foot in his hometown.

One of the largest ethnic groups in Afghanistan, the Hazaras, began fleeing genocide as early as the 1900s after years of discrimination and persecution for being Shia Muslims.

Tahirian travelled to Afghanistan once before, but due to a labyrinth of rebel-held checkpoints, it was too dangerous to venture further than the capital, Kabul.

‘If they know that you are Hazara, they will shoot you straight away. They are trying to vanish us from the map of Afghanistan,’ says Tahirian.

After being systematically targeted by the Taliban, Hazaras began to flee to Iran and Pakistan in search of safety. But safety was not to be found for Tahirian and his family.

Radical Sunni groups target Hazaras in Quetta, Pakistan, and deadly suicide bomb attacks and target killings have become a regular occurrence.

‘I was two to three metres away from the blasts. The whole streets were full of broken glass, and people were screaming. We were collecting body parts for 200 yards.’

Tahirian is still transported back to the disastrous scene when opening up about his past.

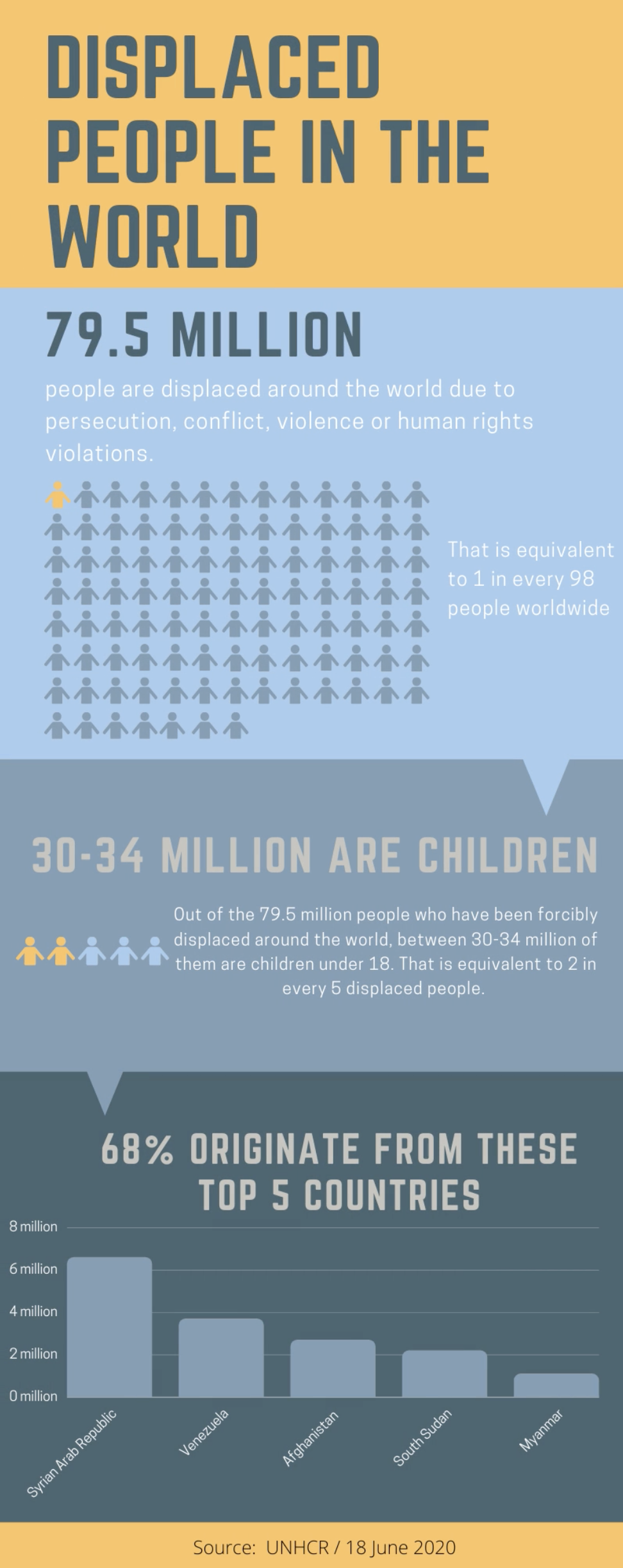

Last year UNHCR recorded a staggering number of forcibly displaced people, tallying over 79 million. War, disaster and poverty have resulted in families all over the world having to find safety in countries other than their own.

The Toll Of Freedom

International development and humanitarian aid worker and researcher, Daniel McAvoy, has over 20 years of experience working in the humanitarian field.

During the 1999 conflict in Kosovo, McAvoy worked in the largest refugee camp in Macedonia, supporting and distributing food to the 45,000 people who had fled the war.

McAvoy recalls seeing the emotional and physical toll fleeing conflict can have on people. The shock of what is happening lasts days before their resilience begins to kick in.

‘[There is a] threat of violence, loss of freedom... risk of hunger or even severe famine. If you can’t work, you can’t protect your family, and that can really undermine people’s personal identities,’ says McAvoy.

Since the Arab Spring in 2010, there has been a steady increase of refugees around the globe, mainly originating from Syria. Substantial conflicts have led to significant episodes of displacement, and global warming is predicted to have a disastrous impact on the rising number of refugees and displaced people.

‘If you imagine trying to make the decision to leave your family home, comfortable bed, everything you own and most of your wealth and take your chances trying to escape to another country, it’s a situation that’s almost impossible to imagine if you haven’t had to live through it.’

Searching For Solace

In 2017, after years of being targeted by radical Sunni extremists, Tahirian's family fled violence to seek refuge in Australia. Faced with the grave decision to leave his family, Tahirian's father journeyed by sea to search for a land that could offer solace for himself and his family.

Driving Taxis With A PhD

Director of CREATE (Center for Refugee Employment, Advocacy, Training and Education), Alexander Newman, is a researcher of best practice in supporting people to re-establish their careers while seeking refuge in a new country.

Unemployment rates for refugees are increasing due to qualifications not being recognised in the Australian system. Newman and his team at CREATE have found a gap in the system for highly skilled migrants.

‘With a lot of agencies putting people in jobs such as catering, cleaning and aged care, we focus on the higher end—people with university background qualifications. There are a lot of people with a refugee background that are underemployed; they are driving taxis with a PhD. We are wasting some of that talent.’

CREATE’s career clinic is one of the most successful programs they have implemented to support people from a refugee background. CREATE not only focuses on helping people transition into employment, they also educate and encourage employers to hire people from refugee backgrounds.

‘[Businesses] think it is hard because of the visa issues, the government doesn’t make it easy, but there is no restriction on hiring people on bridging visas or temporary visas. It’s about educating managers that it’s not as hard as they might think. It’s part of your social inclusion strategy,’ says Newman.

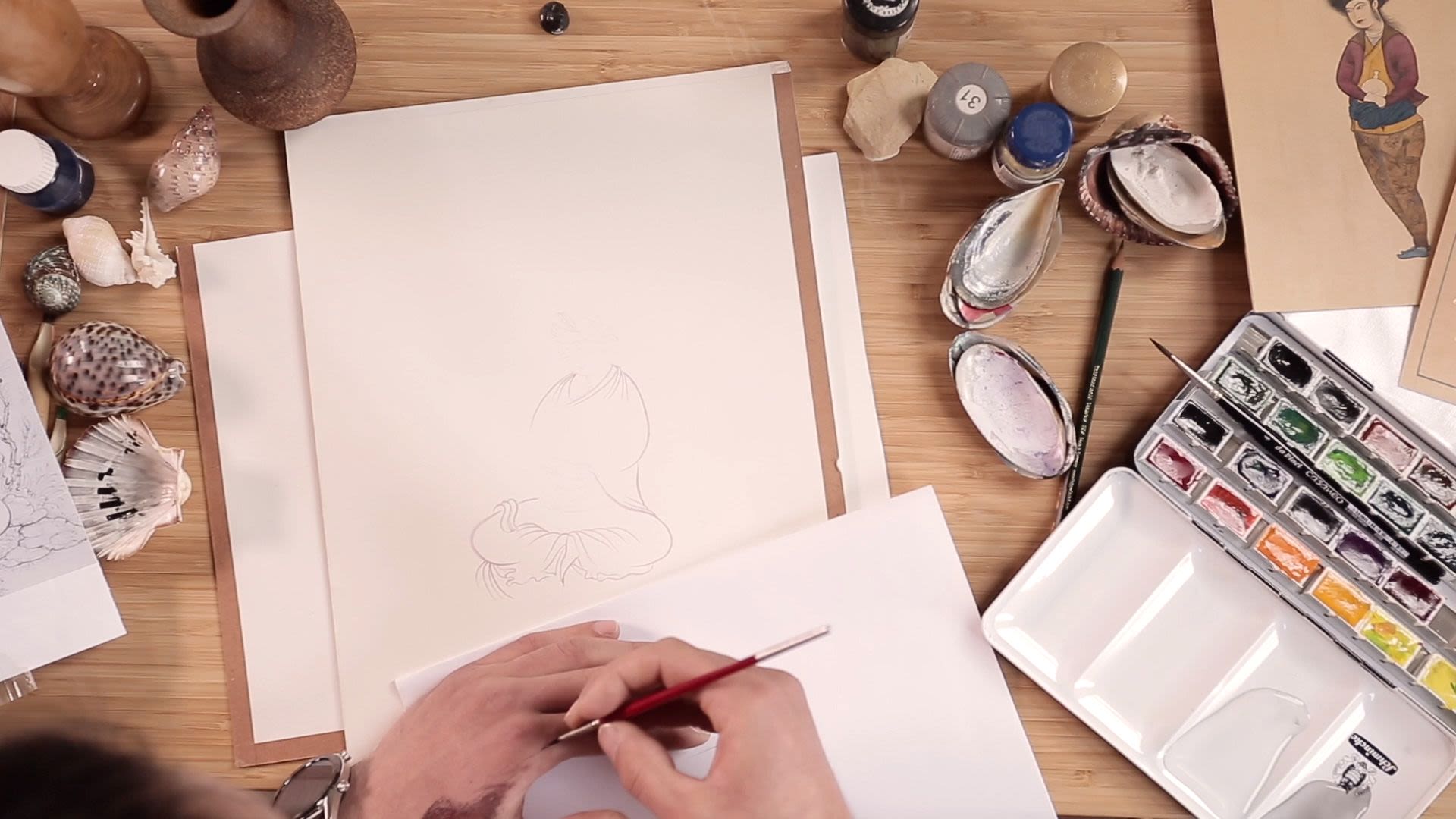

Tahirian is a self-taught artist. His work has been in numerous art exhibitions since moving to Australia in 2017.

In an attempt to feel a connection to his homeland, Tahirian practices the traditional miniature technique that originated in Persia during the 13th century.

Life in Australia offers Tahirian and his younger siblings the opportunity to follow their dreams, a concept that is unattainable in Pakistan.

The Conversation Must Change

Strategic communications consultant Anat Shenker-Osorio has completed extensive research on messaging issues surrounding immigration. Her research focuses on the effects of changing language to be more inclusive.

‘Social science research has long demonstrated that when some group is viewed as “other”, the majoritarian population will accept and even champion mistreatment of them,’ says Shenker-Osorio.

Shenker-Osorio believes that without changing the perception of groups deemed as ‘other’, there will be no way to ‘enact progressive policies and to elect progressive leaders.’ By targeting and blaming a specific group for hardship, politicians can ‘divide and conquer’.

‘As long as any right-wing government has a scapegoat, they can both perpetrate harms against this group, and they can keep working people from coming together in sufficient numbers to demand actual solutions that would make life better for everyone,’ says Shenker-Osorio.

But there is hope...

Shenker-Osorio believes that public opinion began to shift in 2016, during the period of #LetThemStay and #BringThemHere. During 2018, at the height of #KidsOffNauru, there was another positive shift towards acceptance of people seeking asylum.

‘Research and polling indicated a double-digit improvement in perceptions of people seeking asylum and desire for solutions that respect people’s rights - no matter their colour, creed or place of origin,’ says Shenker-Osorio.

A New Perspective

COVID-19 could offer Australians an insight into what refugees have been facing for so many years. With restricted travel, curfews and separation from family, the public may be able to form a new perspective of what it is like to be displaced.

‘The situation with COVID-19 has been a huge wake-up call for everybody. I’d like to think the fear, uncertainty, lack of freedom and the choices that we are experiencing in our lives will make us see the plight of refugees from a new perspective.’

However, McAvoy is still not convinced that this will create change. McAvoy addresses the fact that ‘history tells us that when societies are fearful and uncertain, they tend to be more susceptible in believing the worst in other people.’

The Chance For A New Beginning

Australia has offered Tahirian the chance to build a new life, away from the horrors of target killings and bomb blasts.

Although haunting memories of Tahirian's past still linger in his subconscious, his passion for art and desire for a new beginning outweigh the horrors that once engulfed his life.

Tahirian is currently working to support his family so that his younger siblings can follow their dreams and attend university. Since arriving in Australia, they can leave their home knowing that at night they will safely return, a fundamental human right that they will never take for granted.

Photography, video and text by Rochelle Hansen